STILL CRAZY AFTER ALL THESE YEARS

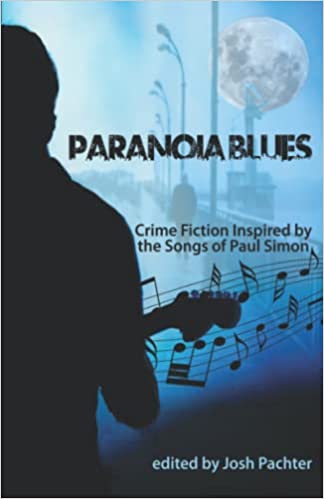

(published in Paranoia Blues, 10/31/22, ed. by Josh Pachter)

by E.A. Aymar

We see the moment the woman realizes she’s going to die. The fear behind her eyes comes forward and she bucks hard against the chair she’s tied to in the living room. She desperately casts about, looking for something that might save her. For someone.

But the only people here are me and my sister Callie.

She starts to give us the answers we want, tells us who she is, who she works with. She tells us about her son, that she misses him. That hunting us was a mistake. She can’t control her crying. Her face is a blur of tears.

Over the past year, my sister and I have seen a lot of people die.

None of them have gone with grace.

Callie pulls out her knife, and the begging turns to screaming.

Normally we’d gag her, but this cabin we found—nicely furnished, probably a rental property we were lucky to stumble on—is buried deep in one of Maryland’s forests. The closest neighbor is miles away.

I leave her with Callie, head to the kitchen, pull a bottle of water from the fridge.

Drinking water calms me, like the way other people count to ten, or list items in a room, or tap their fingertips together, or pray.

The water fills my mouth. The plastic bottle crumples in my hand.

Callie washes her knife and hands and wrists in the bathroom sink.

“Ella es simpatica,” she remarks, her back to me as I sit on the lip of the tub. She’s been practicing her Spanish, getting ready for Panama.

“Yeah.”

She flips off the water. “Adios, señora Aberdeen.”

“Aberdeen?”

She switches to English. “Wasn’t that her name?”

“We’re in Aberdeen, dummy. Her name was Chloe.”

“Really? I kept saying ‘Goodbye, Aberdeen.’” Callie snaps her fingers. “That must be why she looked so confused!”

“At least we know for sure she was working with the Daughters.”

“They’re never going to stop, huh?”

“No.”

Ever since Callie murdered one of their members, the Daughters have been after us.

“Oh, well,” Callie says, and she switches back to Spanish. “¿Baltimore es mañana por la noche, si?”

“Baltimore is tomorrow night,” I confirm. “And the ship leaves Wednesday afternoon.”

“Estoy emocionada,” she says. “Yo no visito Panama por años.”

“You were a baby when mom took us.”

She ignores me. “I wonder if we’ll fit in. At least I sort of speak the language.”

“Yeah, but you don’t know anything about the country. Who’s the president?”

“They don’t have a king?”

“Cortizo. What’s the capital?”

“The … Canal? I don’t know, Vic. You can write the book report, but I’ll do the talking. Deal?”

“To be fair,” I say, to end the bickering, “neither of us really belongs there. Even though mom was from there.”

“I’ve always felt that way,” Callie says. She peers into the mirror, touches the blood in her hair.

The fire starts before sunrise.

Four in the morning, and a long finger of smoke reaches down my throat. I roll out of bed, coughing, palms pressed into my eyes, elbows and knees on the floor.

Someone pulls me to my feet. Callie. Her shirt’s lifted over her nose like a makeshift hospital mask, her backpack slung over her shoulder.

“The Daughters,” she says.

I reach under the bed, grab my own bag. We stumble out of the bedroom, Callie first, me following with a hand on her shoulder. We hear the fire but don’t see it, the cabin crackling as flames chew through wood. The world is smoky and blurry but visible.

We drop to our knees and crawl, breathe close to the floor. The cabin’s front door is ahead of us. We see the orange light of fire in the living room. Heat wets our skin.

Callie reaches for the front door, unlocks it, turns the knob. And something occurs to me, something I should have realized sooner.

I pull her to the ground as gunshots explode over us. Slam the door as bullets rip through the house.

“We probably shouldn’t go that way,” Callie says.

“You think?”

We crawl back down the hall. I tap my sister on the side, motion her to follow me to the kitchen. We stay away from the smoke. I yank open the fridge, grab a bottle of water, twist it open, pour half over my face and into my mouth, give the rest to Callie.

She douses herself and tosses the empty bottle away. “What now?”

“They’ll be at the back door, too.”

She slips her bag off her shoulder. “Do we shoot our way out?”

“We won’t make it off the porch.”

“So, what then?”

“Hold on,” I say. “I’m thinking.”

But I’m not thinking of a way out.

I’m remembering what got us here.

The dead woman in the other room. All of Callie’s murders. The ones I’ve accepted, the ones I’ve assisted. We’ve spent a lot of time close to death this past year, couldn’t keep any of the Daughters we captured alive because they knew too much about us. We have reasons for the killings.

Those reasons used to be enough.

“Vic,” Callie says. Her voice brings me back.

“The window,” I tell her. “We’ll go through the window.”

She stares at me. “You remember we’re on a hill, right? The drop is, like, two stories.”

“There’s no doors on this side of the house. They won’t be watching.”

“Shit.” Callie scrambles to her feet, slides open the glass, pushes out the screen.

“I don’t see anyone,” she tells me.

Smoke curls into the room, like a hand reaching under the doorway. I feel it wrapping around my neck. Squeezing.

We climb onto the counter. My knees press hard against the granite. The fire has reached the kitchen, clawed through the wall separating this room from the living room. The dead woman’s body is on the floor, her skin burning away.

Callie grabs my shoulder.

She’s sitting on the windowsill like she’s about to parachute out.

“Vic, come on.”

She disappears into the darkness.

After a few seconds, I do the same.

Sunlight wakes me.

I grab my knee with both hands, pull it to my stomach. Squeeze with everything I’ve got until the pain shrinks to a small throbbing ball, stops hammering my heart, my blood, my brain.

“You’re up.”

Callie’s voice. I turn from the sun. She’s sitting on the ground, staring at me curiously.

We’re in the woods.

“My leg,” I explain.

“You landed funny,” Callie says. “Well, not funny. Okay, kinda funny? Your leg just went out underneath you and you rolled down the hill. But you stopped when your head hit a tree.”

“What?”

Callie nods. “Then I dragged you like a mile. I’m a hero.”

“What?”

“Stop saying what,” Callie says. “Can we talk about something else?”

Later, as the light fades, the pain gets worse.

“¡Por favor, déjame ir!”

I sit up, see a scared man tied to a tree.

“Who’re you?” I ask.

“¿Que?”

“What?”

“Your Spanish is getting better!” Callie sings out. “Yay!”

I rub my eyes. “Who is this guy?”

He’s older, short and chubby with curly black hair. His chin is shaking. Eyes impossibly wide.

“He was with you when I came back from the grocery store.”

“Grocery store?”

“That’s what you said the last time you woke up,” Callie chides me. “When I gave you your medicine.”

“You did?” Everything is fuzzy, sleepy.

But my leg doesn’t hurt.

Not until I try to stand.

“I don’t know what you did,” Callie says, after I’m done rolling on the ground and yelling. “I don’t think it’s broken, but it’s worse than a sprain. Sproken? Is that a medical term? Or brain? No, that’s stupid. It’s sproken.”

The waves of pain recede. I lift my face from the ground. Spit blood.

“Who’s he?” I ask.

“Someone we can’t let go,” Callie tells me.

As if he realizes we’re talking about him, the man starts speaking again. “Mi bolsillo.”

“¡Cállate!” Callie tells him, and her voice is as sharp and sudden as a shovel striking dirt.

“Mi bolsillo,” he says again, quieter.

Callie reaches into his pocket and pulls out a photo. She glances at it, tosses the picture on the ground.

I crawl over to the photo, my head and leg aching with each movement. See a picture of a boy, maybe six or seven years old.

“Mi hijo.”

Callie ignores him. “He was just standing here,” she tells me. “I went to the store, and then I came back and saw him.”

“¡Por favor!”

Clouds gather behind my eyes. “We should let him go.” I stand and walk toward the man and try to untie his knots.

Or I think I do.

But I’m still sitting on the ground. I haven’t moved.

“I don’t think I’m well,” I announce.

“¡Por favor!”

I lie down.

“I don’t think you’re supposed to sleep when you have a concussion,” Callie tells me, right before my eyes close.

When I wake the next morning, she’s ripping the guy’s photograph to pieces.

I feel rested, recovered enough to realize I’m not going to pass out again. The pain in my leg has lessened. I stand slowly and walk, leaning on trees for support.

The dizziness has decreased.

I touch the back of my head, feel something soft. A bandage.

“He told me what to do,” Callie says, when I ask her about it. “He told me to sit you up, lean you against a tree. Put a bandage on, so there wouldn’t be any infection.”

“I feel better,” I tell her.

“There’s another ship leaving for Panama tomorrow afternoon. I bought tickets with his credit card.”

“Okay.”

Callie hands me my backpack. I carefully sling it over my shoulders. I lean against her as we walk through the woods.

I don’t look back at the body.

*

Baltimore is a thirty-dollar cab ride away. A taxi isn’t exactly an inconspicuous way to travel, but we don’t have much of a choice.

Callie chats with the driver the entire time. I stare out the window.

He drops us off outside a bar about a mile from the port. It’s the first time I’ve been in Baltimore since I was a kid. Twenty-four years of life circling back on itself, a snake nibbling its own tail.

“Is it really sproken?” Callie asks, watching as I examine my leg.

“Maybe it’s a torn ACL? But I’m not sure what that means.”

Callie is staring at my face. “You’re sweating.”

“I need something to drink.”

We head into the bar, sit in a dark booth away from the windows. I drink myself a beer and then down Callie’s. The cold air in the bar and the alcohol make me even more tired, as if riding in the cab and hobbling here are the end of a long, exhausting day.

“This meal will take the last of our cash,” Callie says. “And I’m too nervous to use that dude’s credit card again.”

I wipe the sweat off my face with a napkin. Nod.

“Are you going to throw up? You look like you’re going to throw up.”

“Maybe.”

A love song is playing quietly on the jukebox. I don’t know it.

A waitress brings crab cakes for Callie and a hamburger for me. The burger is the best thing I’ve ever tasted.

Callie picks at her crab cake.

“What’s going on?” I ask.

“Nothing.”

“Doesn’t feel like nothing.”

“Honestly, I’m okay.”

“You know you could tell me if you weren’t.”

“I know.”

“But would you?”

“Nah.”

“Great.”

“I feel bad about Raúl,” Callie says.

“Who?”

“The guy in the woods.” Callie is picking at her food, pushing it around her plate. “I didn’t have to kill him.”

We’re the only people in the restaurant, except for a bored hostess typing on her phone.

“These people are giving up their lives for us,” Callie goes on. “Like the stories I’ve read about human sacrifices. The Aztecs or Incas or whatever, they didn’t want to die. A king or a priest just killed them. And it didn’t even matter in the end, because now all of them are long gone, even the kings. Everything fades.”

“I don’t get what you’re saying.”

“All those people dead, Vic, and none of it mattered. Maybe that’s what we’re doing. Following a fake god. We think we’re doing what we need to do to stay safe, but it’s been the same craziness since day one.”

I try to think of the right thing to say. I’ve never heard Callie like this.

“I shouldn’t have killed her,” she says. Her eyes are crimson. “I loved her.”

“You didn’t have a choice.”

“That night when I called you,” she says, “and you came over, and you saw her body. Do you remember that night?”

I wipe my forehead with another napkin. Nod. “You told me she wanted you to join the Daughters,” I say. “You said no. It turned into a fight.”

“I didn’t—I didn’t want that to happen,” Callie says. “I was happy, so was she. But they were such a part of her. That stupid militia. She went on and on about overthrowing the government and sovereignty, whatever that is. Like, all that wasn’t just a part of her, Vic. It was her. She talked and talked and I told her she was crazy and she slapped me. And I laughed and she hit me again. I couldn’t stop, even though it was everything I worried about, everything I was afraid of. But I kept laughing. I couldn’t stop fucking laughing, even when she was choking me. I laughed until I had to fight back.” She picks up an empty beer glass, gazes into it. “Maybe I was wrong.”

Something in her voice reminds of that scared child I’ll always remember, long ago, the little girl who desperately needed help. The child I stole away from our father’s fists and lips.

“Was I wrong?”

“If they knew the truth,” I tell her, speaking carefully, “everything that happened, no one would blame us for any of this.”

She just smiles.

*

We sleep with the other homeless in a park near the port, surrounded by tents and sleeping bags and blankets. The night isn’t cold, and the grass is as comfortable as the forest was. Which isn’t comfortable at all, but Callie and I are used to it.

The next morning, we cross the street to the port. The ship we’re going to board is large, with a decorative whale fin arced in the back. A crowd of passengers wait to file up the gangway.

“We don’t look like them,” I observe.

“You think we’ll stick out?” She still has that seriousness from the day before. Rain in her eyes.

“Yes.”

She points to restroom doors on the side of the building. “Let’s freshen up.”

A guy is leaving the men’s room as I walk in. There are two stalls and three urinals. A long mirror over a pair of sinks. I splash water on my face, look at my clothes. My rough appearance doesn’t surprise me. The age in my face does. I don’t look like me.

I clean up as best as I can, use wet paper towels to wipe dirt stains from my shirt and tamp down my hair.

I walk outside and lean against the wall next to the ladies’ room.

It takes Callie a few minutes, but she finally emerges.

“Vic.”

She drops to a knee, her hand over her stomach.

Her hand and stomach are red.

The next moments blur. I don’t remember helping her back inside the restroom, rushing to the sink.

I’ve never seen this much blood.

I lock the restroom door.

Kneel next to my sister.

Callie’s lying on her back. With every breath, blood is wrung from her stomach.

The dead woman on the tile floor has a neck cut so deep her head barely seems to be hanging on.

“I didn’t see her follow you in.”

“Yeah, I—” Pain contorts Callie’s face and voice. “Me, neither.”

“What do I do?” I ask, helplessly. I look down at my hands, gently covering the wound in my sister’s stomach.

The bathroom doorknob shakes.

“It’s broken!” I shout.

“I want to go to Panama,” Callie whispers.

I see the fear in her face.

The same fear we’ve seen in so many others.

The moment the ship docks at the Canal, police speaking Spanish arrest me, hand me over to police speaking English. They drive me to an airport, lead me to a small plane on the runway.

As we walk from the car to the plane, I can feel the Panamanian air. That touch of wetness in the wind. Warm rain. Like a memory from a time I can’t quite remember.

I must have had this same kind of moment years ago.

The law has me. They have me for the dozen or so women we killed, although no one refers to them as the Daughters. It’s like the militia doesn’t exist, never has. They even have me for the man in the woods.

The families of the dead are constantly on the news, weeping. I’m told by my guards that the country wants to kill me. I’m told pictures of me and Callie are everywhere, every news channel. Callie is pictured as my helpless younger sister, forced into killing by her malevolent older brother.

They blame me for all the deaths, even Callie’s.

I don’t fight it.

There’s no hiding anymore. I’m alone in a cell. Around me, men talk. They talk to themselves or each other, they laugh, threaten, shout, scream. One of them prays, loudly and passionately and desperately to God, until they take him away and his voice is forever stopped.

Tonight another prisoner shouts to God, and I close my eyes and lie on my cot. My time is up. I spent weeks in a courtroom while a jury peered at me, sometimes with curiosity, often with hate. I knew they would convict me. And now they’re going to fill my body with poison.

I don’t know where you are, Callie.

I don’t know if I’ll see you again.

But I do have that one moment, that moment in the warm rain, that moment all these years later that connects me to you and takes me somewhere else.

Before we ran.

Before we killed.

Before the poison filled our bodies, all those years ago.